As Originally Posted to the Wall Street Journal

The recipients of U.S. visas for specialized job functions are a small blip in the overall employment market. But they've taken on great symbolic importance in the past year.

The recipients of U.S. visas for specialized job functions are a small blip in the overall employment market. But they've taken on great symbolic importance in the past year.

With the filing period for employers beginning April 1, immigration advocates argue that granting more H-1B visas to foreign nationals creates jobs for Americans. Critics dispute that notion and say that financial firms receiving bailout funds have been hiring foreign workers while laying off tens of thousands of Americans. Both sides are playing fast and loose with the numbers.

"It's another form of March Madness," says Gordon Day, president of IEEE-USA, a professional association for engineers. Every year, "partisans on both sides of the immigration debate try to interpret every bit of data available to support their case."

Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates, New York mayor Michael Bloomberg and Republican Senator Judd Gregg of New Hampshire all have cited a study they claim shows that each one of these visas awarded to technology companies creates five jobs. Mr. Gates interpreted the study in testimony to Congress last year as finding that "for every H-1B holder that technology companies hire, five additional jobs are created around that person."

But the study shows nothing of the kind. Instead, it finds a positive correlation between these visas and job growth. These visas could be an indicator of broader hiring at the company, rather than the cause.

Click Image to Enlarge

Some think the claim that the study, conducted by the pro-immigration National Foundation for American Policy, demonstrates awarding visas boosts hiring is way off base. It "has all the scientific sense of cold fusion," says Harvard University economist Richard B. Freeman, "though of course it could be we have discovered the perpetual employment expansion elixir."

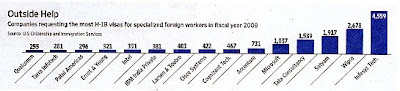

There are other problems with the study: It's confined to S&P 500 technology companies. That excludes the leading users of these visas, mainly Indian technology companies such as Infosys Technologies, Wipro Technologies and Satyam Computer Services. The analysis is based on changes in global employment, rather than just domestic employment. And the study also uses an indirect measure: letters seeking approval for visas, rather than the visas themselves.

Stuart Anderson, executive director of the Arlington, Va., foundation that conducted the study, said these limitations arose from the data available. He said the proxy used for visas rendered the findings conservative, since some firms file multiple letters for the same worker.

Representatives for Mr. Gates declined to comment. Representatives for Mr. Bloomberg and Mr. Gregg didn't respond to inquiries.

Some researchers find the general premise of the study persuasive, even if the study didn't prove it. Duke University statistician David Banks said correlation can't prove causation, but he did think the study "corroborates the idea that H-1B visas support job creation." It does so, he says, by contradicting the theory that companies seek foreign workers to replace domestic ones. Vivek Wadhwa, a senior research associate at Harvard, pointed to other studies that have shown positive relationships between immigration and innovation. But these generally lacked a hook as catchy as five-for-one.

An Associated Press article provided a hook for opponents of the visa program in today's lean economic climate. The AP reported in February that the dozen U.S. banks receiving the most bailout funds had requested visas for more than 21,800 workers over the last six years, but maybe a fraction were hired. Days later, Bernie Sanders, an independent senator from Vermont, was citing the report -- and modifying its conclusions.

"What has been the response of Wall Street to the loss of 100,000 of their own workers?" Sen. Sanders said, citing layoff figures from the last three months of 2008. "What these banks have announced is they are requesting 21,000 foreign workers over the next six years through the H-1B program to fill those jobs." Yet the six-year period in AP's study ended just as that period of layoffs began.

Confusion over the AP stats reflects the somewhat murky nature of H-1B visas. The visas last for three years and can be extended to six years. Employers begin by applying to the Labor Department for each potential hire, sending multiple applications if the worker may be based in various locations. Once those are approved, employers petition U.S Citizenship and Immigration Services for the visa, which is generally granted unless the cap of 65,000 is reached.

The AP wasn't counting petitions but the larger number of applications since these data were more readily available. Mr. Anderson, however, counted fewer than 1,000 petitions granted to 12 of the largest bailout recipients in 2008. He also compared the number of workers receiving visas last year to the total work force, finding it was fewer than 1% for each bank.

Sen. Sanders's co-sponsor on an amendment restricting banks' use of the visas, Republican Sen. Charles Grassley of Iowa, also confused the number of applications with the number of workers. Sen. Grassley's spokeswoman didn't respond to a request for comment.

While the AP may have double- or triple-counted some prospective workers, Mr. Anderson, in turn, may have overplayed his hand. As an AP spokesman noted, Mr. Anderson initially counted zero visas for Capital One rather than 104, because he misspelled the bank's name as "Capitol One." Also, it would have been fairer to compare the visa numbers to new hires, instead of comparing them to the total work force, as he did.

Several banks corroborated the notion that this isn't a major source of employees, though no bank would fully provide all relevant numbers. A Citigroup spokeswoman said holders of H-1B visas account for fewer than 1% of all employees; the equivalent figure was fewer than 0.04% at Wells Fargo. A Bank of America spokeswoman said such workers accounted for fewer than 1% of new hires last year. No bank would say how many such workers its contractors use.

"The major abuse occurs not with the banks' direct hires of H-1Bs but instead their shadow work forces," says Ron Hira, an assistant professor of public policy at Rochester Institute of Technology.

Ted Bridis, head of the AP's Washington Investigative Team, notes that the AP sought information from banks, including on third-party workers, but was rebuffed. AP spokesman Paul Colford says, "The AP stands by its scrupulous, rigorous reporting."

Others have backed off -- a bit. Warren Gunnels, senior policy advisor to Sen. Sanders, acknowledged that the AP numbers covered the last six years, and may overstate actual hiring of foreign workers. Then he suggested that the numbers, though they were used to back the amendment requiring banks to prove they can't find qualified Americans, aren't critical.

Even if alternative, lower numbers such as Mr. Anderson's are more accurate, "why would the supporters of increasing H-1B visas be so concerned about our amendment?" Mr. Gunnels asks. "At a time when the unemployment rate is soaring, do you really think there aren't enough intelligent Americans to fill these jobs?"